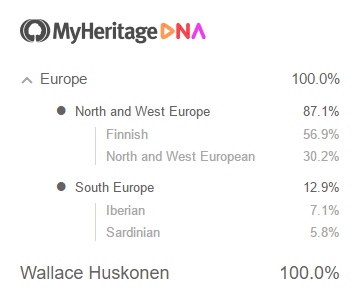

This year, 2017, is the centennial year of Finland’s independence. This has peaked my interest in learning more about the history of the country of my paternal grandparents. It is timely therefore that the March 2017 issue of Finnish American Reporter published an article about that history. According to an Editor’s Note accompanying the article, it was compiled from several entries about Finland on the website Wikipedia. The Note also points out that Compiler Kaj Rekola modified some of the material to enhance readability and flow.

Following Finland’s Path to Independence

Historical evidence shows that Finland became the eastern part of the Swedish realm around the year 1250. The term Sweden-Finland has been coined to indicate that Finland was an integral part of the kingdom, not a colony or a separate province as some nationalistic historians have claimed. The Baltic and the Gulf of Bothnia did not separate but rather connected the western and eastern part of the Kingdom ol Sweden.

Already in the 1500s. Turku was the second-largest city in the kingdom. The king’s subjects in both parts of the realm had exactly the same rights and responsibilities. The 600-year Swedish rule ended with the so-called Finnish war in 1808-1809.

Under Tsarist Russia

In 1809. Russia attacked Sweden at the behest of emperor Napoleon, to punish Sweden for refusing to join Napoleon’s continental blockade against Great Britain, a conflict that became later known as the “Finnish War.” In 1809, the lost territory of Sweden became the Grand Duchy of Finland in the Russian Empire when the Finnish Diet, assembled in Porvoo, recognized Czar Alexander I as Grand Duke of Finland, thus replacing the Swedish king as the ruler.

For his part, Alexander confirmed the rights of the Finns, in particular, promising freedom to pursue their customs and religion and to maintain their identity, saying: “Providence having placed us in possession of the Grand Duchy of Finland, we have desired by the present act to confirm and ratify the religion and the fundamental laws of the land, as well as the privileges and rights which each class in the said Grand Duchy in particular, and all the inhabitants in general, be their position high or low, have hitherto enjoyed according to the constitution. We promise to maintain all these benefits and laws firm and unshaken in their full force.”

This promise was maintained by all successors to the Russian throne (as Grand Dukes of Finland); indeed, Czar Alexander II even amplified the powers of the Finnish Diet in 1869. The status of Finland as an autonomous Grand Duchy was unique within the Russian empire. It enjoyed its own government, kept the Swedish-era laws, Lutheran religion, had its own army, and, since 1864, its own currency, and a customs border against Russia. The Russian czar was the head of state as the Grand Duke of Finland, resembling the role of the English sovereign in relation to Canada or Australia.

The policy of Russification of Finland

The “Russification of Finland” policy (1899-1905 and 1908-1917) was a governmental policy of the Russian Empire aimed at limiting the special status of the Grand Duchy of Finland and possibly terminating its political autonomy and cultural uniqueness. It was part of a larger policy of Russification pursued by late 19th-early 20th century Russian governments, which tried to abolish cultural and administrative autonomy of non-Russian minorities within the empire. The two Russification campaigns evoked widespread Finnish resistance, starting with petitions and escalating to strikes, passive resistance (including draft resistance) and eventually active resistance. Finnish opposition to Russification was one of the main factor that ultimately led to Finland’s declaration of independence in 1917.

The February Manifesto of 1899

The February Manifesto was an imperial decree which Czar Nicholas II issued on 15 February 1899. It was the starting point of the implementation of the Russification policy. Having enjoyed prosperity and control over their own affairs, and having remained loyal subjects for nearly a century, the manifesto was cause for Finnish despair.

The manifesto was forced through the Finnish senate by the deciding vote of the senate president, an appointee of the tsar–and after the governor-general of Finland, Nicolay Bobrikov, had threatened a military invasion and siege. While ostensibly affirming the Finns’ rights in purely local matters, the manifesto asserted the authority of the Russian state in any and all matters, which could be considered to “come within the scope of the general legislation of the empire.”

Russification policies enacted included:

– The February Manifesto asserted the I imperial government’s right to rule Finland without the consent of local legislative bodies, under which:

– Only Russian currency and stamps were allowed;

– Russian was made official language of administration (in 1900, there were an estimated 8,000 8,000 Russians in all of Finland, of a population of 2.700,000).The Finns saw ‘this as placing the Russian minority in charge;

– The Orthodox Russian Church was the church of state, including, for example, criminalizing the act of subjecting a follower of the Orthodox Church to a Lutheran church service;

– The Press was subject to Russian censorship;

– The Finnish army was made subject to Russian rules of military service.

– The Language Manifesto of 1 900, the decree by Emperor Nicholas II, which made Russian the language of administration of Finland.

– The conscription law, signed by Nicholas II in July 1901 incorporating the Finnish army into the imperial army. This triggered a surge in the emigration of conscripting age young men who feared being sent to the Russo-Japanese war, which raged in 1904-05.

From April 1903 until the Russian Revolution of 1905, the governor-general was granted dictatorial powers. In June 1904 Eugen Schauman assassinated Bobrikov, the incumbent governor-general. The imperial government responded with a purge of opponents of Russification within the Finnish administration and more stringent censorship. However the resistance campaign also had some successes, notably a de facto reversal of the new conscription law.

The Russification campaign was suspended and partially reversed in 1905-07 during a period of civil unrest throughout the Russian empire following Russian defeats in the Russo-Japanese War. In Finland, a unicameral democratic parliament elected through universal suffrage (the first in Europe), replaced the Swedish era Diet comprising the four estates (the nobility, clergy, burgers, and peasants). The Russian government’s reversal calmed the revolutionary fervor – for a while.

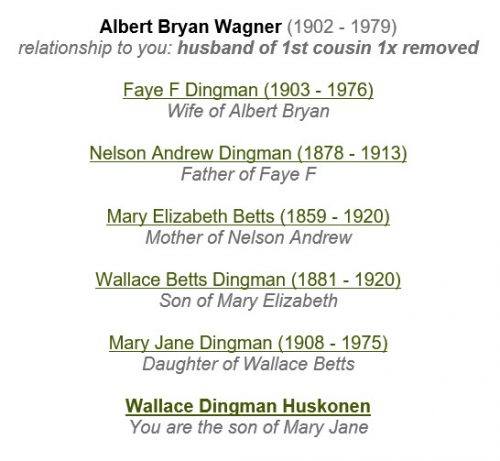

The turmoil during the initial period of Russification probably contributed to my grandfather’s decision to sell his farm in 1902 and move his family to America. Evert Huuskonen probably didn’t face conscription, but other elements of Russification probably would have bothered him.

The more we learn about the times of our ancestors, the more we understand why they did some of the things they did during their lifetimes.

One more note: Kaj Rekola is a professional translator specializing in translating Finnish and Swedish to English. He lives in Mountain View, California.

Recent Comments